January 19, 2026

- seedfoundation

- Leave a Comment on Reaching the Last Mile: Why Affordable Non-State Schools Matter for Lagos’ Out-of-School Children

A Shared Urgency We Cannot Ignore

Lagos State sits at the heart of Nigeria’s economic promise and at the centre of one of its most persistent education challenges. Thousands of children across the state remain out of school, not because education is unwanted, but because access, capacity, and system design have not kept pace with rapid urban growth, migration, climate shocks, and poverty.

In recent years, renewed attention has been placed on the Out-of-School Children (OOSC) challenge, with ambitious targets and financing mechanisms emerging to support reintegration at scale. This is welcome and necessary. Yet as implementation conversations advance, one critical question deserves more careful attention: how do we ensure that delivery plans are grounded in the realities of where children actually live and how education access currently functions?

This is not a question of ideology or sectoral preference. It is a question of last-mile delivery.

The Delivery Constraint We Rarely Name

Public education systems carry the primary responsibility for guaranteeing access to education. In Lagos, the state government has made significant investments in expanding public school infrastructure, teacher recruitment, and policy reforms. These efforts matter deeply.

However, delivery constraints remain, particularly in fast-growing, low-income communities. In some areas, public schools are already operating at or beyond capacity. In others, distance, safety concerns, or the pace of population growth limit effective access for children who need immediate placement.

When OOSC reintegration targets are set without sufficient attention to absorptive capacity, implementation risks become inevitable. Children may be identified, enrolled on paper, but struggle to remain in school if systems are overstretched or geographically misaligned.

This gap between policy ambition and delivery reality is where well-intentioned programmes can falter.

The Invisible Delivery Platform in Plain Sight

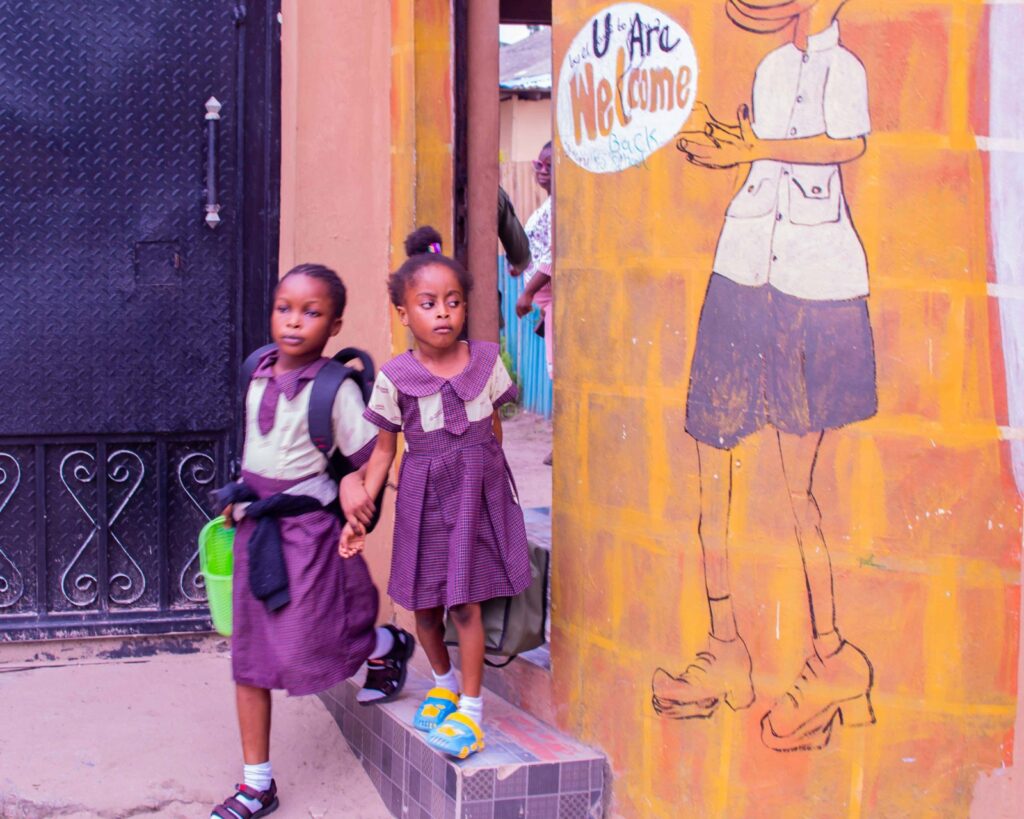

Across Lagos State, thousands of affordable non-state schools operate within the same communities where OOSC are most concentrated. These schools are typically small and locally rooted, serving families who fall between public provision and high-end private education.

Despite their scale and proximity, these schools are often absent from formal delivery conversations on OOSC reintegration. Their exclusion is rarely framed as a deliberate policy choice; instead, it emerges from legacy assumptions about quality, regulation, or the boundaries of public responsibility.

Yet from a systems perspective, these schools represent something else entirely: existing delivery infrastructure.

They have classrooms, teachers, daily attendance routines, and trust relationships with parents. In many cases, they are the only schools within walking distance for children in informal settlements or underserved peri-urban areas.

From SEED’s ongoing engagement with affordable non-state schools across Lagos’ 20 Local Government Areas, emerging patterns indicate that these community-embedded schools are present in the same neighbourhoods where out-of-school children are most often concentrated. Many report enrolling learners who had previously dropped out due to household shocks such as loss of income or displacement, underscoring how proximity and flexibility influence school reintegration.

This alignment between school presence and out-of-school populations suggests delivery opportunities that existing strategies may not yet fully leverage.

Ignoring this reality does not make it disappear, it simply shifts pressure onto already constrained public systems.

What Emerging Evidence from Lagos Is Telling Us

Over the past decade, SEED Care & Support Foundation has worked closely with affordable non-state schools, school associations, parents, and community leaders across Lagos’ 20 Local Government Areas (LGAs). Through surveys, programme implementation, coalition work, and policy engagement, several consistent insights have emerged.

First, many OOSC are not entirely disconnected from education. Instead, they move in and out of schooling due to cost shocks, flooding, displacement, health issues, or household instability. Flexible, community-based schooling options often determine whether these children re-enter and remain in school.

Recent displacement events in waterfront and informal settlements across Lagos illustrate how sudden housing disruptions can translate into learning interruption. When households are required to relocate, even temporarily, children may fall out of school due to distance, documentation gaps, loss of income, or uncertainty around re-enrolment.

These displacement-related interruptions often occur more rapidly than formal systems can respond. In many affected areas, nearby public schools are already operating close to capacity, limiting immediate reintegration options. The result is a short- to medium-term increase in out-of-school children, concentrated in communities already facing access constraints.

In such contexts, affordable non-state schools frequently function as informal stabilisers, providing flexible entry points, maintaining learning continuity and absorbing learners while households navigate resettlement. This role is rarely reflected in planning assumptions, yet it has direct implications for how OOSC delivery strategies account for mobility and urban shocks.

For example, a primary-age child who had been out of school for over a year after a household income shock was quickly reintegrated into learning through a nearby affordable non-state school. By adjusting enrolment expectations and providing short-term learning support, the school enabled the child to rejoin their peers without waiting for bureaucratic approvals or long public school waitlists; illustrating how flexible, localised delivery can make the difference between exclusion and sustained re-engagement.

Second, affordable non-state schools already absorb a significant number of children who would otherwise remain excluded. This happens quietly, without public financing, and often without formal recognition.

Third, where quality concerns exist (and they do) these are not arguments for exclusion but for engagement, support, and accountability. Systems improve what they choose to include.

These insights echo broader reflections previously shared on the invisibility of certain schools and children within national education narratives. When data, policy, and financing frameworks overlook entire segments of the delivery ecosystem, children served by those segments become easier to ignore.

At the national level, part of the implementation challenge reflects how education data systems categorise and count schools. When systems do not fully capture the scale and activities of affordable non-state provision, this can skew interpretations of where delivery capacity exists and how progress toward universal basic education, including Sustainable Development Goal 4, is tracked and resourced.

Inclusion as a Delivery Decision, Not an Ideological One

Discussions about affordable non-state schools are often framed as debates about privatisation versus public education. This framing is unhelpful in the context of OOSC delivery.

The more relevant question is simpler and more pragmatic: what combination of delivery channels will reach the most children, safely, equitably, and sustainably?

In contexts where public schools have space and proximity, they should absolutely remain the primary reintegration pathway. In contexts where they do not, excluding other regulated, community-based options introduces unnecessary bottlenecks.

In this sense, inclusion is not an endorsement of one sector over another. It is a recognition that systems function through multiple, interconnected actors, especially in complex urban environments like Lagos.

A Moment of Choice for OOSC Delivery in Lagos

As new financing mechanisms and implementation programmes take shape, Lagos stands at a pivotal moment. Decisions made now about eligibility, partnerships, and delivery pathways will determine whether OOSC targets are merely announced or actually achieved.

There is a quiet but important difference between designing programmes for systems and designing them with systems as they currently exist. The latter requires acknowledging informal realities, engaging non-traditional actors, and building safeguards rather than walls.

Affordable non-state schools are not a silver bullet. But neither are they a marginal footnote. They are part of the education ecosystem that already serves low-income families at scale.

The question, therefore, is not whether they should replace public education but whether ignoring them helps or hinders the goal we all share: ensuring that every child in Lagos can access meaningful learning.

Closing Reflection: Designing for Reality

OOSC challenges are rarely solved by ambition alone. They are solved by alignment between policy, financing, infrastructure, and lived experience.

If we design reintegration strategies around assumptions rather than realities, children pay the price. If, however, we design with openness to existing delivery platforms, while insisting on quality, accountability, and child protection, we increase our chances of success.

The last mile of education delivery is not abstract. It is a classroom. A teacher. A school gate that opens every morning.

As Lagos continues to expand its ambition for OOSC reintegration, the systems question is not ideological but practical: .. are delivery strategies being designed around existing capacity, or around assumptions that delay access for the very children they aim to serve, especially in a city where mobility, climate shocks, and urban redevelopment continue to reshape where and how children can access learning?

** This article reflects SEED’s evidence-informed engagement in ongoing education policy reform processes.